Sitting at my computer in my comfortable office, handling herbarium specimens that are often well over a hundred years old, I sometimes forget how dangerous it could be to collect these specimens in the 1800’s, and how many of these collectors came to bad—and sometimes violent—ends. One such end inspired a story by Rudyard Kipling.

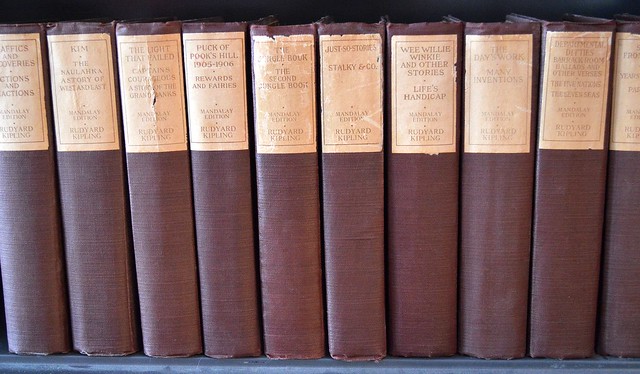

I have a 1925 edition of the works of Rudyard Kipling, given to me by my father a few years ago. He had picked up the books at an estate sale in Syracuse over half a century ago; for years they languished in one of my family's bookcases, unread by anybody. At the age of 9 or 10, inspired by the Disney movie, I finally cracked one of them open to read The Jungle Book (which proved very different from the movie) and The Second Jungle Book, as well as Kipling's Just-So Stories. I've only recently read The Man Who Would Be King, although I saw the 1975 movie with the same title years ago. Both the novella and the movie end with a rather memorable scene of a man’s severed head in a bag, a scene loosely based on the true story of Adolphe Schlagintweit.

Kipling probably never met any of the Schlagintweit brothers—Hermann (1826-1882), Adolphe* (1829-1857), and Robert (1833-1885)—but recently I've been handling some of the plant specimens these Bavarian explorers collected in the 1850's on a scientific expedition to Asia. Well-educated sons of a wealthy Munich ophthalmologist, Hermann and Adolphe moved to Berlin in 1849 shortly after receiving their doctorates in geography and geology, respectively. There they met the famous naturalist and explorer Alexander von Humboldt, then 80 years old and looking for younger men to continue his life's work. Impressed by their previous work in the Alps, he recommended them for an expedition commissioned by the East India Company (and paid for in part, for reasons not clear to me, by the King of Prussia) to complete the Magnetic Survey of India and to collect geological, zoological, botanical, and anthropological specimens. In 1854, taking their younger brother Robert along as an assistant, they set off for India.

This expedition was significant for going into areas where no collectors had been before, and in many cases no westerners of any kind. For three years the brothers traveled both together and separately, with a retinue of assistants and servants, finally writing about their travels in a never-completed series of volumes, "Results of a scientific mission to India and High Asia". For Adolphe, the botanist of the team, the publication was posthumous.

Die Gebrüder Schlagintweit, 1847 (source: Wikimedia)

In the course of my work in the United States National Herbarium I've handled thousands of specimens, but the ones from the Schlagintweit expedition are unlike any others. All are mounted on paper that is both smaller and flimsier than standard herbarium sheets, with collection data printed directly on the sheets. The majority were collected in India (including areas now in Pakistan) with forays into Tibet and Nepal. British India and Tibet were both a bit fuzzy and disputed around the edges, and these uncertain boundaries, the political tensions they engendered, and ongoing territorial skirmishes among the various local tribes were among the obstacles the brothers had to contend with.

A typical Herbarium Schlagintweit specimen in the U.S. National Herbarium

The oldest brother, Hermann, was not quite 30 when they went on this expedition, and Adolphe only about 25. The three brothers began the expedition together, traveling sometimes together and sometimes separately over the next two years. In December 1856 the brothers met in Raulpindi (now Rawalpindi, Pakistan) and then parted company one final time, with Hermann and Robert returning to Europe in early 1857. Adolphe stayed behind, traveling instead to Peshaur (now Peshawar, Pakistan), with plans to go to Turkestan and Tibet before returning to Europe. That was the last they saw of him; in 1857 he disappeared and was reportedly murdered but for several years, his fate was uncertain.

The brothers were later able to ascertain that in August 1857, Adolphe made his way to Kashgar, a Tibetan city near the borders of present-day Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. The region was claimed by China but had been recently occupied by an invader from neighboring Kokand, the infamously cruel Khoja Vali Khan (Wali Khan in modern spellings). By all accounts Vali Khan was a brutal leader, whose favorite treatment of his enemies was beheading. Travelers returned with tales of heads stacked in roadside pyramids. Upon his arrival in Kashgar, Adolphe was taken prisoner and for reasons that are still uncertain, but possibly suspecting him of spying for China, Vali Khan ordered Adolphe beheaded.

The demise of Adolphe Schlagintweit was widely reported, first as a rumor with the hope that he might still turn up, and later as fact, in various natural history journals. Hermann and Robert gathered all the first-and second-hand reports that they could find on Adolphe's fate (in particular Adolphe's assistants and servants, who had escaped), and like all of their scientific measurements and observations, published them all in excruciating and often redundant detail in the first and second volumes of their reports. The second volume included some last-minute new information on the recovery of Adolphe's journal and head.

A critical detail the modern stories leave out is that not one but two different heads were produced as allegedly being the remains of Adolphe. The first, reported by T.H. Thornton, personal assistant to the Judicial Commissioner of Punjab, was produced by one of Adolphe's surviving servants but had apparently been obtained some time after the fact and under questionable circumstances. It proved after a detailed examination by two doctors in Lahore to be that of a native, albeit one who had been violently decapitated. The second head had been delivered to Lord William Hay, Deputy Commissioner of Simla, in Srinigar, Kashmir, by a Persian trader along with Adolphe's previously missing final journal. Traveling through Kashgar, and knowing of the story, the trader had been able to locate and purchase Adolphe's journal (saving it from being used as packing paper for snuff) as well as provide additional details about Adolphe's death. He had also traced Adolphe's head to the field of a melon-grower, who had buried it and showed him where to dig. Lord Hay reported this in a letter to the brothers in September 1861 but aware of the previous head, he was somewhat cautious that this was indeed the head of Adolphe Schlagintweit. Lord Hay added with some hint of satisfaction that "The Khója [Vali Khan] was soon after driven out of Káshgar by the Chinese, and is now wandering about a miserable drunkard without a single follower."

It's not clear whether the second head was ever determined to be that of Adolphe. Neither is it clear what happened to either head, but these notorious stories would have been in recent memory when Kipling arrived in British India in the 1880's. His travels included Lahore and Simla, and he may well have met some of the people directly involved. The story apparently resonated with Kipling, who used the delivery of a severed head to a British civil servant in India as a key detail in his 1888 story.

Watercolor by Hermann Schlagintweit. Palmyra palm trees (Borassus flabellifer) near Madras, India (1855) Source: Wellcome Library, London

Although the Schlagintweit brothers' reports were deemed "unreadable" by one English reviewer, and the Magnetic Survey of India later fizzled into nothing, their collections remain an important contribution to science. The brothers collected an enormous number of specimens, in addition to hundreds of sketches and watercolors (Hermann in particular was apparently an excellent artist). The collections were sent to Berlin, with the bulk of them later sent to England for distribution. About 900 of the botanical specimens are now housed in the United States National Herbarium.

For a detailed discussion of the Schlagintweit brothers and their mission, see "Conquerors of The Künlün"? The Schlagintweit Mission to High Asia, 1854-57 by Gabriel Finkelstein.

*Although most modern sources spell his name "Adolf", I've used "Adolphe" throughout, as this is the spelling used in the publications by the brothers themselves, as well as in contemporary reports about them.

Very Interesting, you should put this in the Plant Press

ReplyDeleteWhat an intersting read! Thanks.

ReplyDeleteIn the Alpine Museum of Munich there is a current wonderful exhibition on the Schlagwintweits, with a catalogue published. A colleague in Munich (Bernhard Dickoré) is working on the botany of the Schlagintweits.

ReplyDeleteExhibition (in German):

http://www.alpenverein.de/kultur/sonderausstellung-im-alpinen-museum-ueber-den-himalaya-die-expedition-der-brueder-schlagintweit-nach-indien-und-zentralasien-1854-bis-1858_aid_15146.html

Regards

Hajo Esser (esser@bsm.mwn.de)

Specimens discovered as part of a project to curate foreign specimens held in the State Botanical Collection include 54 sheets collected by the Schlagintweit brothers. These are lodged in the Herbarium (MEL) at the Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria in Melbourne.

ReplyDeleteVery interesting, indeed, as are the comments. Great movie, too!

ReplyDeleteWhat's interesting about those early explorers is how brave they were and absolutely determined to collect and document as many plants as possible. The plants we take for granted often have very bloody beginnings. Excellent post!

ReplyDeleteVery interesting. Thanks for the very informative post!

ReplyDeleteIntriguing account. I'm amazed Humboldt made it to 80!

ReplyDeleteAbsolutely fascinating!

ReplyDelete